Visual Art in Outdoor Setting Nov 2019 Sc or Ga

| Georgia O'Keeffe | |

|---|---|

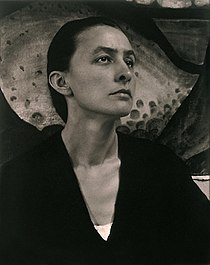

O'Keeffe in 1918, photograph past Alfred Stieglitz | |

| Born | Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (1887-11-15)November 15, 1887 Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, U.Southward. |

| Died | March 6, 1986(1986-03-06) (aged 98) Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.South. |

| Education | School of the Art Institute of Chicago Columbia College Teachers Higher, Columbia Academy University of Virginia Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | American modernism, Precisionism |

| Spouse(s) | Alfred Stieglitz (m. 1924; died ) |

| Family | Ida O'Keeffe (sister) |

| Awards | National Medal of Arts (1985) Presidential Medal of Liberty (1977) Edward MacDowell Medal (1972) |

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (November 15, 1887 – March six, 1986) was an American modernist artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O'Keeffe has been chosen the "Mother of American modernism".[i] [2]

In 1905, O'Keeffe began fine art training at the School of the Fine art Institute of Chicago[iii] and then the Art Students League of New York. In 1908, unable to fund further education, she worked for two years every bit a commercial illustrator and then taught in Virginia, Texas, and South Carolina between 1911 and 1918. She studied fine art in the summers between 1912 and 1914 and was introduced to the principles and philosophies of Arthur Wesley Dow, who created works of art based upon personal style, blueprint, and interpretation of subjects, rather than trying to copy or represent them. This caused a major change in the manner she felt nigh and approached art, as seen in the start stages of her watercolors from her studies at the University of Virginia and more dramatically in the charcoal drawings that she produced in 1915 that led to total abstraction. Alfred Stieglitz, an art dealer and photographer, held an exhibit of her works in 1917.[4] Over the next couple of years, she taught and continued her studies at the Teachers College, Columbia University.

She moved to New York in 1918 at Stieglitz'south request and began working seriously equally an artist. They developed a professional person and personal relationship that led to their wedlock in 1924. O'Keeffe created many forms of abstract art, including close-ups of flowers, such as the Red Canna paintings, that many establish to represent vulvas,[5] though O'Keeffe consistently denied that intention.[6] The imputation of the depiction of women's sexuality was as well fueled by explicit and sensuous photographs of O'Keeffe that Stieglitz had taken and exhibited.

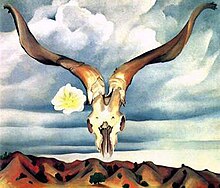

O'Keeffe and Stieglitz lived together in New York until 1929, when O'Keeffe began spending part of the year in the Southwest, which served every bit inspiration for her paintings of New United mexican states landscapes and images of animal skulls, such as Cow'southward Skull: Carmine, White, and Blue and Ram's Head White Hollyhock and Petty Hills. Later on Stieglitz's death, she lived in New United mexican states at Georgia O'Keeffe Home and Studio in Abiquiú until the last years of her life, when she lived in Santa Atomic number 26. In 2014, O'Keeffe's 1932 painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No. ane sold for $44,405,000, more than iii times the previous world auction record for whatever female creative person.[7] Afterward her death, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum was established in Santa Fe.

Early on life [edit]

Georgia O'Keeffe was born on November 15, 1887,[two] [8] in a farmhouse in the boondocks of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin.[9] [ten] Her parents, Francis Calyxtus O'Keeffe and Ida (Totto) O'Keeffe, were dairy farmers. Her father was of Irish gaelic descent. Her maternal grandad, George Victor Totto, for whom O'Keeffe was named, was a Hungarian count who came to the The states in 1848.[2] [11]

O'Keeffe was the 2d of seven children.[2] She attended Town Hall Schoolhouse in Sun Prairie.[12] By age x, she had decided to become an artist,[13] and with her sisters, Ida and Anita,[xiv] she received fine art instruction from local watercolorist Sara Mann. O'Keeffe attended high school at Sacred Heart Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, as a boarder between 1901 and 1902. In late 1902, the O'Keeffes moved from Wisconsin to the close-knit neighborhood of Peacock Hill in Williamsburg, Virginia, where O'Keeffe'southward father started a business organization making rusticated cast concrete cake in anticipation of a demand for the block in the Peninsula building merchandise, but the demand never materialized.[15] O'Keeffe stayed in Wisconsin with her aunt attention Madison Central High School[16] until joining her family in Virginia in 1903. She completed high school as a boarder at Chatham Episcopal Institute in Virginia (now Chatham Hall), graduating in 1905. At Chatham, she was a member of Kappa Delta sorority.[2] [12]

O'Keeffe taught and headed the art department at West Texas State Normal College, watching over her youngest sibling, Claudia, at her mother's request.[17] In 1917, she visited her brother, Alexis, at a military camp in Texas earlier he shipped out for Europe during World War I. While there, she created the painting The Flag,[eighteen] which expressed her anxiety and depression about the war.[xix]

Career [edit]

Education and early career [edit]

Georgia O'Keeffe, Untitled, 1908, Art Students League of New York collection

From 1905 to 1906, O'Keeffe was enrolled at the School of the Art Establish of Chicago, where she studied with John Vanderpoel and ranked at the top of her class.[two] [13] Equally a consequence of contracting typhoid fever, she had to take a year off from her education.[2] In 1907, she attended the Art Students League in New York City, where she studied under William Merritt Chase, Kenyon Cox, and F. Luis Mora.[2] In 1908, she won the League's William Merritt Chase even so-life prize for her oil painting Expressionless Rabbit with Copper Pot. Her prize was a scholarship to attend the League's outdoor summer school in Lake George, New York.[2] While in the New York City, O'Keeffe visited galleries, such as 291, co-owned by her futurity husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The gallery promoted the work of avant-garde artists and photographers from the Usa and Europe.[2]

In 1908, O'Keeffe discovered that she would not be able to finance her studies. Her father had gone bankrupt and her mother was seriously ill with tuberculosis.[two] She was non interested in a career as a painter based on the mimetic tradition that had formed the basis of her fine art training.[13] She took a task in Chicago as a commercial artist and worked there until 1910, when she returned to Virginia to recuperate from the measles[20] and subsequently moved with her family to Charlottesville, Virginia.[ii] She did not pigment for four years and said that the smell of turpentine made her sick.[xiii] She began teaching art in 1911. Ane of her positions was at her former school, Chatham Episcopal Institute, in Virginia.[two] [21]

She took a summer art class in 1912 at the University of Virginia from Alon Bement, who was a Columbia University Teachers Higher faculty member. Under Bement, she learned of the innovative ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow, Bement'south colleague. Dow's approach was influenced by principles of blueprint and composition in Japanese art. She began to experiment with abstract compositions and develop a personal fashion that veered away from realism.[ii] [thirteen] From 1912 to 1914, she taught art in the public schools in Amarillo in the Texas Panhandle, and was a didactics assistant to Bement during the summers.[two] She took classes at the Academy of Virginia for two more summers.[22] She too took a class in the spring of 1914 at Teachers College of Columbia University with Dow, who further influenced her thinking about the process of making fine art.[23] Her studies at the University of Virginia, based upon Dow's principles, were pivotal in O'Keeffe's development every bit an creative person. Through her exploration and growth as an artist, she helped to institute the American modernism move.

She taught at Columbia College in Columbia, S Carolina in late 1915, where she completed a series of highly innovative charcoal abstractions[xiii] based on her personal sensations.[21] In early 1916, O'Keeffe was in New York at Teachers College, Columbia University. She mailed the charcoal drawings to a friend and former classmate at Teachers Higher, Anita Pollitzer, who took them to Alfred Stieglitz at his 291 gallery early in 1916.[24] Stieglitz found them to exist the "purest, finest, sincerest things that had entered 291 in a long while", and said that he would like to show them. In April that yr, Stieglitz exhibited ten of her drawings at 291.[2] [13]

Afterwards further course work at Columbia in early on 1916 and summertime education for Bement,[2] she became the chair of the art department at Due west Texas State Normal Higher, in Canyon, Texas kickoff in the fall of 1916.[25] She began a series of watercolor paintings based upon the scenery and expansive views during her walks,[21] [26] including vibrant paintings of Palo Duro Coulee.[27] O'Keeffe, who enjoyed sunrises and sunsets, developed a fondness for intense and nocturnal colors. Building upon a practice she began in South Carolina, O'Keeffe painted to express her near private sensations and feelings. Rather than sketching out a design before painting, she freely created designs. O'Keeffe continued to experiment until she believed she truly captured her feelings in the watercolor, Light Coming on the Plains No. I (1917).[21] She "captured a monumental mural in this elementary configuration, fusing bluish and greenish pigments in almost indistinct tonal graduations that simulate the pulsating result of lite on the horizon of the Texas Panhandle," according to author Sharyn Rohlfsen Udall.[21] [26] Subsequently her relationship with Alfred Stieglitz started, her watercolor paintings concluded quickly. Stieglitz heavily encouraged her to quit because the use of watercolor was associated with amateur women artists.[28]

New York [edit]

Stieglitz, 24 years older than O'Keeffe,[28] provided financial back up and arranged for a residence and place for her to paint in New York in 1918. They adult a close personal relationship while he promoted her work.[2] She came to know the many early on American modernists who were office of Stieglitz's circle of artists, including painters Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and photographers Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. Strand'southward photography, as well as that of Stieglitz and his many photographer friends, inspired O'Keeffe'due south work. As well around this time, O'Keeffe became sick during the 1918 flu pandemic.[11]

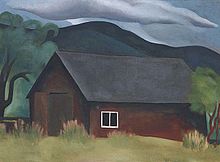

O'Keeffe began creating simplified images of natural things, such as leaves, flowers, and rocks.[29] Inspired by Precisionism, The Green Apple tree, completed in 1922, depicts her notion of unproblematic, meaningful life.[30] O'Keeffe said that year, "it is only by option, past elimination, and by emphasis that we go at the real meaning of things."[30] Bluish and Greenish Music expresses O'Keeffe's feelings about music through visual art, using bold and subtle colors.[31]

As well in 1922, journalist Paul Rosenfeld commented "[the] Essence of very womanhood permeates her pictures", citing her utilise of colour and shapes as metaphors for the female torso.[32] This same commodity too describes her paintings in a sexual way.[32]

O'Keeffe, most famous for her delineation of flowers, made virtually 200 blossom paintings,[33] which by the mid-1920s were large-scale depictions of flowers, as if seen through a magnifying lens, such as Oriental Poppies [34] [35] and several Ruddy Canna paintings.[36] She painted her first large-scale flower painting, Petunia, No. 2, in 1924 and it was first exhibited in 1925.[2] Making magnified depictions of objects created a sense of awe and emotional intensity.[29] On Nov twenty, 2014, O'Keeffe's Jimson Weed/White Bloom No i (1932) sold for $44,405,000 in 2014 at auction to Walmart heiress Alice Walton, more than iii times the previous earth auction tape for any female creative person.[37] [38]

Art historian Linda Nochlin interpreted Black Iris Three (1926) equally a morphological metaphor for a vulva, but O'Keeffe rejected that estimation, claiming they were but pictures of flowers.[39] [40]

After having moved into a 30th floor apartment in the Shelton Hotel in 1925,[41] O'Keeffe began a series of paintings of the city skyscrapers and skyline.[42] Ane of her most notable works, which demonstrates her skill at depicting the buildings in the Precisionist manner, is the Radiator Building – Night, New York.[43] [44] Other examples are New York Street with Moon (1925),[45] The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y. (1926),[46] and City Night (1926).[2] She made a cityscape, E River from the Thirtieth Story of the Shelton Hotel in 1928, a painting of her view of the Eastward River and fume-emitting factories in Queens.[42] The adjacent year she made her last New York Urban center skyline and skyscraper paintings and traveled to New Mexico, which became a source of inspiration for her work.[43]

In 1924, Stieglitz arranged a simultaneous exhibit of O'Keeffe'due south works of fine art and his photographs at Anderson Galleries and bundled for other major exhibits.[47] The Brooklyn Museum held a retrospective of her work in 1927.[24] In 1928, Stieglitz appear that 6 of her calla lily paintings sold to an anonymous buyer in French republic for US$25,000, but there is no evidence that this transaction occurred the way Stieglitz reported.[ commendation needed ] As a result of the press attention, O'Keeffe'south paintings sold at a higher price from that betoken onward.[48] [49] By the late 1920s she was noted for her piece of work depicting American subjects, particularly for the paintings of New York metropolis skyscrapers and close-upwards paintings of flowers.[47]

Taos [edit]

O'Keeffe traveled to New United mexican states by 1929 with her friend Rebecca Strand and stayed in Taos with Mabel Contrivance Luhan, who provided the women with studios.[50] From her room she had a clear view of the Taos Mountains as well as the morada (meetinghouse) of the Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno aka the Penitentes.[51] O'Keeffe went on many pack trips, exploring the rugged mountains and deserts of the region that summer and later on visited the nearby D. H. Lawrence Ranch,[50] where she completed her now famous oil painting, The Lawrence Tree, currently endemic past the Wadsworth Archives in Hartford, Connecticut.[52] O'Keeffe visited and painted the nearby historical San Francisco de Asis Mission Church at Ranchos de Taos. She made several paintings of the church, as had many artists, and her painting of a fragment of it silhouetted against the heaven captured it from a unique perspective.[53] [54]

New Mexico and New York [edit]

Georgia O'Keeffe, Ram's Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills, 1935, The Brooklyn Museum

O'Keeffe then spent part of almost every year working in New Mexico. She nerveless rocks and bones from the desert floor and made them and the distinctive architectural and landscape forms of the surface area subjects in her work.[29] Known as a loner, O'Keeffe often explored the land she loved in her Ford Model A, which she purchased and learned to drive in 1929. She often talked about her fondness for Ghost Ranch and Northern New Mexico, as in 1943, when she explained, "Such a beautiful, untouched lonely feeling identify, such a fine function of what I call the 'Faraway'. It is a place I have painted earlier ... fifty-fifty now I must do it again."[54]

O'Keeffe did not work from tardily 1932 until about the mid-1930s [54] as she endured various nervous breakdowns and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital.[28] These nervous breakdowns were the result of O'Keeffe learning of her husband'due south affair.[28] She was a popular creative person, receiving commissions while her works were existence exhibited in New York and other places.[55] In 1936, she completed what would become ane of her all-time-known paintings, Summer Days. Information technology depicts a desert scene with a deer skull with vibrant wildflowers. Resembling Ram'south Caput with Hollyhock, it depicted the skull floating above the horizon.[55] [56]

Pineapple Bud, 1939, oil on sheet

In 1938, the advertising agency N. W. Ayer & Son approached O'Keeffe virtually creating two paintings for the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (now Dole Nutrient Visitor) to use in advertising.[57] [58] [59] Other artists who produced paintings of Hawaii for the Hawaiian Pineapple Visitor's advertising include Lloyd Sexton, Jr., Millard Sheets, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Isamu Noguchi, and Miguel Covarrubias.[60] The offer came at a critical fourth dimension in O'Keeffe's life: she was 51, and her career seemed to be stalling (critics were calling her focus on New Mexico limited, and branding her desert images "a kind of mass product").[61] She arrived in Honolulu February 8, 1939, aboard the SS Lurline and spent 9 weeks in Oahu, Maui, Kauai, and the island of Hawaii. By far the most productive and vivid period was on Maui, where she was given consummate freedom to explore and paint.[61] [62] She painted flowers, landscapes, and traditional Hawaiian fishhooks. Dorsum in New York, O'Keeffe completed a serial of 20 sensual, verdant paintings. However, she did not paint the requested pineapple until the Hawaiian Pineapple Company sent a plant to her New York studio.[63]

O'Keeffe's "White Place", the Plaza Blanca cliffs and badlands almost Abiquiú

During the 1940s, O'Keeffe had two ane-adult female retrospectives, the first at the Art Institute of Chicago (1943).[29] Her second was in 1946, when she was the offset adult female artist to have a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Fine art (MoMA) in Manhattan.[33] Whitney Museum of American Art began an endeavor to create the showtime catalogue of her work in the mid-1940s.[55]

In the 1940s, O'Keeffe made an all-encompassing series of paintings of what is chosen the "Black Place", about 150 miles (240 km) west of her Ghost Ranch house.[64] O'Keeffe said that the Black Place resembled "a mile of elephants with gray hills and white sand at their feet."[54] She made paintings of the "White Place", a white rock formation located near her Abiquiú firm.[65]

Abiquiú [edit]

| External images | |

|---|---|

| | |

| |

In 1946, she began making the architectural forms of her Abiquiú house—patio wall and door—subjects in her work.[66] Another distinctive painting was Ladder to the Moon, 1958.[67] O'Keeffe produced a serial of cloudscape art, such every bit Sky higher up the Clouds in the mid-1960s that were inspired by her views from airplane windows.[29]

Worcester Art Museum held a retrospective of her work in 1960[24] and 10 years subsequently, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted the Georgia O'Keeffe Retrospective Exhibition.[47]

In 1972, O'Keeffe lost much of her eyesight due to macular degeneration, leaving her with only peripheral vision. She stopped oil painting without assistance in 1972.[68] In the 1970s, she made a series of works in watercolor.[69] Her autobiography, Georgia O'Keeffe, published in 1976 was a best seller.[47]

Judy Chicago gave O'Keeffe a prominent identify in her The Dinner Political party (1979) in recognition of what many prominent feminist artists considered groundbreaking introduction of sensual and feminist imagery in her works of art.[70] Although feminists celebrated O'Keeffe as the originator of "female iconography",[71] O'Keeffe refused to bring together the feminist art move or cooperate with whatsoever all-women projects.[72] She disliked beingness called a "woman artist" and wanted to be considered an "creative person."[73]

She continued working in pencil and charcoal until 1984.[68]

O'Keeffe's Flowers as Vulvas and Criticism [edit]

O'Keeffe's lotus paintings may have deeper ties to vulvar imagery and symbolism. In Egyptian mythology, lotus flowers are a symbol of the womb, and in Indian mythology, they are direct symbols for vulvas.[74]

Fine art dealer Samuel Kootz was i of O'Keeffe'south critics who, although considering her to be "the only prominent woman artist" (in the words of Marilyn Hall Mitchell), considered sexual expression in her piece of work (and other artists' work) artistically problematic.[75] Kootz stated that "exclamation of sex tin merely impede the talents of an artist, for it is an deed of defiance, of grievance, in which the consciousness of these qualities retards the natural assertions of the painter".[75]

O'Keeffe stood her ground against sexual interpretations of her work, and for fifty years maintained that there was no connection between vulvas and her artwork.[75] Firing back against some of the criticism, O'Keeffe stated, "When people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they're really talking about their own affairs."[76] She attributed other artists' attacks on her work to psychological project. O'Keeffe was also seen as a revolutionary feminist; however, the artist rejected these notions, stating that "femaleness is irrelevant" and that "information technology has nothing to exercise with art making or accomplishment."[77]

Awards and honors [edit]

In 1938, O'Keeffe received an honorary degree of "Doctor of Fine Arts" from The Higher of William & Mary.[78] Afterwards, O'Keeffe was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters[24] and in 1966 was elected a Swain of the American University of Arts and Sciences.[79] Amid her awards and honors, O'Keeffe received the M. Carey Thomas Award at Bryn Mawr Higher in 1971 and 2 years after received an honorary degree from Harvard University.[24]

In 1977, President Gerald Ford presented O'Keeffe with the Presidential Medal of Liberty, the highest honor awarded to American civilians.[80] In 1985, she was awarded the National Medal of Arts past President Ronald Reagan.[47] In 1993, she was inducted into the National Women'south Hall of Fame.[81]

Personal life and decease [edit]

Wedlock [edit]

In June 1918, O'Keeffe accepted Stieglitz's invitation to move to New York from Texas after he promised he would provide her with a tranquility studio where she could pigment. Inside a calendar month he took the first of many nude photographs of her at his family's apartment while his married woman was away. His wife returned home once while their session was nonetheless in progress. She had suspected for a while that something was going on between the 2, and told him to stop seeing O'Keeffe or go out. Stieglitz left home immediately and found a identify in the urban center where he and O'Keeffe could live together. They slept separately for more than two weeks. By the cease of the calendar month they were in the aforementioned bed together, and by mid-August when they visited Oaklawn, the Stieglitz family summer estate in Lake George in upstate New York, "they were like ii teenagers in honey. Several times a day they would stitch the stairs to their bedchamber, so eager to brand dear that they would start taking their clothes off equally they ran."

In February 1921, Stieglitz's photographs of O'Keeffe were included in a retrospective exhibition at the Anderson Galleries. Stieglitz started photographing O'Keeffe when she visited him in New York City to see her 1917 exhibition, and continued taking photographs, many of which were in the nude. It created a public awareness. When he retired from photography in 1937, he had made more than than 350 portraits and more 200 nude photos of her.[29] [82] In 1978, she wrote about how afar from them she had become, "When I look over the photographs Stieglitz took of me—some of them more than lx years ago—I wonder who that person is. Information technology is as if in my 1 life I have lived many lives."[83]

Owing to the legal delays caused by Stieglitz's start wife and her family, information technology would take half dozen years before he obtained a divorce. In 1924, O'Keeffe and Stieglitz got married.[47] For the rest of their lives together, their relationship was, "a collusion....a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the virtually part, without the exchange of a give-and-take. Preferring avoidance to confrontation on nearly problems, O'Keeffe was the chief agent of collusion in their union," according to biographer Benita Eisler.[84] They lived primarily in New York City, merely spent their summers at his father's family estate, Oaklawn, in Lake George in upstate New York.[47]

Mental wellness [edit]

O'Keeffe'due south mental health was fragile. In 1928, Stieglitz began a long-term matter with Dorothy Norman, who was also married, and O'Keeffe lost a projection to create a mural for Radio Metropolis Music Hall. She was hospitalized for depression.[29] At the suggestion of Maria Chabot and Mabel Contrivance Luhan, O'Keeffe began to spend the summers painting in New Mexico in 1929.[47] She traveled by train with her friend the painter Rebecca Strand, Paul Strand's married woman, to Taos, where they lived with their patron who provided them with studios.[50]

Hospitalization [edit]

In 1933, O'Keeffe was hospitalized for two months after suffering a nervous breakdown, largely due to Stieglitz'due south affair with Dorothy Norman.[85] She did not paint again until January 1934. In 1933 and 1934, O'Keeffe recuperated in Bermuda and returned to New Mexico in 1934. In Baronial 1934, she moved to Ghost Ranch, due north of Abiquiú. In 1940, she moved into a firm on the ranch property. The varicolored cliffs surrounding the ranch inspired some of her about famous landscapes.[54] Amongst guests to visit her at the ranch over the years were Charles and Anne Lindbergh, vocaliser-songwriter Joni Mitchell, poet Allen Ginsberg, and photographer Ansel Adams.[86] She traveled and camped at "Black Place" often with her friend, Maria Chabot, and later on with Eliot Porter.[54] [64]

Cerro Pedernal, viewed from Ghost Ranch. This was a favorite subject area for O'Keeffe, who in one case said, "Information technology'south my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it"[87] [88]

Painting materials as displayed at the O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, NM

New beginning [edit]

In 1945, O'Keeffe bought a 2d house, an abandoned hacienda in Abiquiú, which she renovated into a home and studio.[89] Shortly afterward O'Keeffe arrived for the summer in New United mexican states in 1946, Stieglitz suffered a cerebral thrombosis (stroke). She immediately flew to New York to exist with him. He died on July 13, 1946. She buried his ashes at Lake George.[90] She spent the side by side three years mostly in New York settling his estate,[29] and so moved permanently to New Mexico in 1949, spending time at both Ghost Ranch and the Abiquiú house that she made into her studio.[29] [47]

Todd Webb, a photographer she met in the 1940s, moved to New Mexico in 1961. He often made photographs of her, every bit did numerous other of import American photographers, who consistently presented O'Keeffe as a "loner, a severe figure and cocky-made person."[91] While O'Keeffe was known to have a "prickly personality," Webb's photographs portray her with a kind of "quietness and calm" suggesting a relaxed friendship, and revealing new contours of O'Keeffe'southward character.[92]

Travels [edit]

O'Keeffe enjoyed traveling to Europe, and effectually the world, beginning in the 1950s. Several times she took rafting trips downwardly the Colorado River,[24] including a trip downwardly the Glen Coulee, Utah, area in 1961 with Webb and photographer Eliot Porter.[54]

Career cease and expiry [edit]

In 1973, O'Keeffe hired John Bruce "Juan" Hamilton every bit a live-in assistant and then a flagman. Hamilton was a potter, recently divorced and broke. This last years companion was 58 years her junior.[93] Hamilton taught O'Keeffe to piece of work with dirt, encouraged her to resume painting despite her deteriorating eyesight, and helped her write her autobiography. He worked for her for 13 years.[29] O'Keeffe became increasingly frail in her late 90s. She moved to Santa Iron in 1984, where she died on March 6, 1986, at the age of 98.[94] Her torso was cremated and her ashes were scattered, as she wished, on the land around Ghost Ranch.[95]

Estate settlement [edit]

Following O'Keeffe's decease, her family contested her will because codicils added to it in the 1980s had left virtually of her $65 million manor to Hamilton. The case was ultimately settled out of court in July 1987.[95] [96] The instance became a famous precedent in estate planning.[97] [98]

Paintings [edit]

-

O'Keeffe, Untitled – vase of flowers, 1903–1905, watercolor on paper, Georgia O'Keeffe Museum

-

O'Keeffe, Cartoon No. ii – Special, 1915, charcoal on laid paper, 23.6 by xviii.2 inches (60 cm × 46.3 cm), National Gallery of Art

-

O'Keeffe, Blue #1, 1916, watercolor and graphite on newspaper, Brooklyn Museum

-

O'Keeffe, Sunrise, 1916, watercolor on newspaper

-

O'Keeffe, Serial i, No. 8, 1918, oil-painting on canvas, xx.0 by 16.0 inches (50.8 cm × 40.half dozen cm), Lenbachhaus, Munich

-

O'Keeffe, A Storm, 1922, pastel on paper, mounted on illustration lath, 18.3 past 24.4 inches (46.four cm × 61.9 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

Legacy [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

O'Keeffe was a legend beginning in the 1920s, known as much for her independent spirit and female role model as for her dramatic and innovative works of art.[95] Nancy and Jules Heller said, "The most remarkable matter nigh O'Keeffe was the audacity and uniqueness of her early work." At that time, even in Europe, there were few artists exploring abstraction. Fifty-fifty though her works may show elements of different modernist movements, such equally Surrealism and Precisionism, her piece of work is uniquely her own way.[99] She received unprecedented acceptance every bit a adult female artist from the fine art world due to her powerful graphic images and within a decade of moving to New York Urban center, she was the highest-paid American woman artist.[100] She was known for a distinctive style in all aspects of her life.[101] O'Keeffe was also known for her relationship with Stieglitz, in which she provided some insight in her autobiography.[95] The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum says that she was one of the first American artists to practise pure abstraction.[two]

Mary Beth Edelson's Some Living American Women Artists / Terminal Supper (1972) appropriated Leonardo da Vinci'due south The Last Supper, with the heads of notable women artists collaged over the heads of Christ and his apostles. John the Campaigner's caput was replaced with Nancy Graves, and Christ's with Georgia O'Keeffe. This image, addressing the part of religious and fine art historical iconography in the subordination of women, became "i of the virtually iconic images of the feminist art movement."[102] [103]

A substantial part of her estate's assets were transferred to the Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation, a nonprofit. The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum opened in Santa Atomic number 26 in 1997.[95] The assets included a big body of her work, photographs, archival materials, and her Abiquiú firm, library, and property. The Georgia O'Keeffe Dwelling house and Studio in Abiquiú was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1998, and is at present owned by the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.[89]

In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 32-cent stamp honoring O'Keeffe.[104] In 2013, on the 100th anniversary of the Arsenal Evidence, the USPS issued a stamp featuring O'Keeffe'south Blackness Mesa Landscape, New Mexico/Out Back of Marie'due south II, 1930 equally part of their Modern Art in America serial.[105]

A fossilized species of archosaur was named Effigia okeeffeae ("O'Keeffe'southward Ghost") in January 2006, "in honor of Georgia O'Keeffe for her numerous paintings of the badlands at Ghost Ranch and her involvement in the Coelophysis Quarry when it was discovered".[106]

In November 2016, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum recognized the importance of her time in Charlottesville by dedicating an exhibition, using watercolors that she had created over three summers. It was entitled, O'Keeffe at the University of Virginia, 1912–1914.[22]

O'Keeffe holds the record ($44.iv million in 2014) for the highest toll paid for a painting by a woman.[107]

In 1991, PBS aired the American Playhouse product A Spousal relationship: Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, starring Jane Alexander as O'Keeffe and Christopher Plummer as Alfred Stieglitz.[108]

Lifetime Idiot box produced a biopic of Georgia O'Keeffe starring Joan Allen as O'Keeffe, Jeremy Irons as Alfred Stieglitz, Henry Simmons every bit Jean Toomer, Ed Begley Jr. as Stieglitz's brother Lee, and Tyne Daly as Mabel Contrivance Luhan. Information technology premiered on September nineteen, 2009.[109] [110]

Publications [edit]

- O'Keeffe, Georgia (1976). Georgia O'Keeffe. New York: Viking Printing. ISBN978-0-670-33710-1.

- O'Keeffe, Georgia (1988). Some Memories of Drawings. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN978-0-8263-1113-nine.

- Giboire, Clive, ed. (1990). Lovingly, Georgia: The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O'Keeffe & Anita Pollitzer . New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-0-671-69236-0.

- O'Keeffe, Georgia (1993). Georgia O'Keeffe : American and modernistic. New Oasis: Yale University. ISBN978-0-300-05581-8.

- Greenough, Sarah, ed. (2011). My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. Vol. Ane, 1915–1933 (Annotated ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Press. ISBN978-0-300-16630-9.

- Buhler Lynes, Barbara (2012). Georgia O'Keeffe and Her Houses: Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu. Harry North. Abrams. ISBN978-1-4197-0394-2.

- Wintertime, Jeanette (1998). My Name is Georgia: A Portrait. San Diego, New York, London: First Voyager Books. ISBN0-15-201649-X.

References [edit]

- ^ a b "Life and Artwork of Georgia O'Keeffe". C-Span. Jan ix, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d eastward f thou h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Georgia O'Keeffe". Biography Channel. A&E Telly Networks. August 26, 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved Jan xiv, 2017.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe | American painter". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Christiane, Weidemann (2008). 50 women artists you should know . Larass, Petra., Klier, Melanie. Munich: Prestel. ISBN978-three-7913-3956-vi. OCLC 195744889. Archived from the original on Apr 4, 2020. Retrieved March four, 2020.

- ^ "An unabashedly sensual approach to a genteel genre". Newsweek. 110: 74–75. November 9, 1987 – via Readers' Guide Abstracts.

- ^ Avishai, Tamar. "Episode 45: Georgia O'Keeffe's Deer'south Skull With Pedernal (1936)". The Lonely Palette (Podcast). Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ Rile, Karen (December 1, 2014). "Georgia O'Keeffe and the $44 Million Jimson Weed". JSTOR Daily . Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Nascency Tape Details". Wisconsin Historical Guild. Archived from the original on Nov 7, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^ "Birthplace of Georgia O'Keeffe". Lord's day Prairie, WI. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017.

- ^ Wisconsin Legislature. 2013–14 Wisconsin Statutes 2013–14 Due south.84.1021 Georgia O'Keeffe Memorial Highway. Archived September 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Roxana Robinson (1989). Georgia O'Keeffe: A Life. University Press of New England. p. 193. ISBN0-87451-906-3.

- ^ a b Nancy Hopkins Reily (2007). Georgia O'keeffe, a Private Friendship: Walking the Lord's day Prairie State. Sunstone Press. p. 54. ISBN978-0-86534-451-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roberts, Norma J., ed. (1988), The American Collections, Columbus Museum of Fine art, p. 76, ISBN0-8109-1811-0

- ^ Canterbury, Sue (2018). Ida O'Keeffe: Escaping Georgia's Shadow. Dallas, Texas: Dallas Museum of Fine art. p. 15. ISBN978-0-300-21456-7.

- ^ "Colonial Williamsburg Inquiry & Education". world wide web.colonialwilliamsburg.org. Archived from the original on Apr 9, 2020. Retrieved Apr 9, 2020.

- ^ "Blogger". accounts.google.com.

- ^ Gerry Souter (2017). Georgia O'Keeffe. Parkstone International. pp. 34–35. ISBN978-5-457-46766-8.

- ^ The netherlands Cotter (Jan 5, 2017). "Globe War I – The Quick. The Dead. The Artists". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2017. Retrieved January xvi, 2017.

- ^ Roxana Robinson; Georgia O'Keeffe (1989). Georgia O'Keeffe: A Life. Academy Press of New England. pp. 191–193. ISBN978-0-87451-906-8.

- ^ Kathaleen Roberts (November 20, 2016). "Never-earlier-exhibited O'Keeffe paintings prove shift to abstraction". Albuquerque Periodical. Archived from the original on Jan 16, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c d eastward Amon Carter Museum of Western Fine art; Patricia A. Junker; Volition Gillham (2001). An American Collection: Works from the Amon Carter Museum. Hudson Hills. p. 184. ISBN978-1-55595-198-6.

- ^ a b "How UVA shaped Georgia O'Keeffe". University of Virginia. November 10, 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January fourteen, 2017.

- ^ Zilczer, Judith (1999). "'Lite Coming on the Plains': Georgia O'Keeffe'due south Sunrise Series". Artibus et Historiae. 20 (40): 193–194. doi:ten.2307/1483675. JSTOR 1483675.

- ^ a b c d east f Eleanor Tufts; National Museum of Women in the Arts; International Exhibitions Foundation (1987). American women artists, 1830–1930. International Exhibitions Foundation for the National Museum of Women in the Arts. p. 81. ISBN978-0-940979-01-7. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved January twenty, 2017.

- ^ Zilczer, Judith (1999). "'Light Coming on the Plains': Georgia O'Keeffe's Sunrise Series". Artibus et Historiae. 20 (40): 191–208. doi:10.2307/1483675. JSTOR 1483675.

- ^ a b Sharyn Rohlfsen Udall (2000). Carr, O'Keeffe, Kahlo: Places of Their Own . Yale Academy Press. p. 114. ISBN978-0-300-09186-1.

- ^ Michael Abatemarco (April 29, 2016). "Birth of the abstruse: Georgia O'Keeffe in Amarillo". Santa Iron New Mexican. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Rathbone, Belinda; Shattuck, Roger; Turner, Elizabeth Hutton; Arrowsmith, Alexandra; West, Thomas (1992). 2 Lives, Georgia O'Keeffe & Alfred Stieglitz: A Conversation in Paintings and Photographs. HarperCollins. ISBN0-06-016895-one. OCLC 974243303.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ballad Kort; Liz Sonneborn (2002). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. New York: Facts on File. p. 170. ISBN0-8160-4397-3.

- ^ a b Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art: guide to the collection. Alabama: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 144. ISBN978-1-904832-77-5. Archived from the original on Dec xviii, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Blueish and Green Music". Fine art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on Jan 12, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Rosenfeld, Paul (October 1922). "The Paintings of Georgia O'Keeffe". Vanity Fair. pp. 56, 112, 114.

- ^ a b Kristy Puchko (Apr 21, 2015). "15 Things You Should Know About Georgia O'Keeffe". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on Jan 31, 2017. Retrieved Jan 14, 2017.

- ^ Liese Spencer (Dec 31, 2015). "From Georgia O'Keeffe to State of war and Peace: Unmissable Arts Events in 2016". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved Jan xiii, 2017.

- ^ Laura Cumming (April vii, 2012). "The 10 best flower paintings – in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on Jan xviii, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ Barbara Buhler Lynes; Jonathan Weinberg; Georgia O'Keeffe Museum (2011). Shared Intelligence: American Painting and the Photograph. Univ of California Press. p. 92. ISBN978-0-520-26906-4.

- ^ "Auction Results – American Art". Sotheby'due south. November xx, 2014. Archived from the original on September xi, 2016. Retrieved Jan nineteen, 2017.

- ^ "Jimson Weed/White Flower No. one, 1932 by Georgia O'Keeffe". www.georgiaokeeffe.net . Retrieved June x, 2020.

- ^ Nochlin, Linda; Reilly, Maura (2015). "Some Women Realists: Role ane". Women artists: the Linda Nochlin reader. pp. 76–85. ISBN978-0-500-23929-two.

- ^ Tessler, Nira (2015). Flowers and Towers: Politics of Identity in the Fine art of the American 'New Adult female' . Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN978-1-4438-8623-9.

- ^ "Manhattan Residences of Georgia O'Keeffe and Patricia Highsmith Published". NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Archived from the original on Dec eighteen, 2019. Retrieved Dec 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986): Eastward River from the Thirtieth Story of the Shelton Hotel, 1928". New Great britain Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Important Art by Georgia O'Keeffe: Radiator Edifice – Night, New York". The Art Story. Archived from the original on January xviii, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Radiator Building – Nighttime, New York". Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe: New York Street with Moon, 1925". Museo Thyssen-Bornemisz. Archived from the original on Dec 19, 2016. Retrieved Jan 17, 2017.

- ^ "The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y., 1926". Fine art Found of Chicago. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 h i Robert Torchia (September 29, 2016). "O'Keeffe, Georgia – Biography". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on January eighteen, 2017. Retrieved Jan 14, 2017.

- ^ Hunter Drohojowska-Philp (2005). Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe. Due west. Due west. Norton. p. 282. ISBN978-0-393-32741-0.

- ^ Vivien Green Fryd (2003). Art and the Crisis of Marriage: Edward Hopper and Georgia O'Keeffe. University of Chicago Press. p. 164. ISBN978-0-226-26654-i.

- ^ a b c Maurer, Rachel. "The D. H. Lawrence Ranch". University of New Mexico. Archived from the original on June 25, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Richmond-Moll, Jeffrey. "Georgia O'Keeffe, Blackness Cross with Stars and Blue" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2019.

- ^ "The Lawrence Tree". Wadsworth Athenaeum. Hartford, Connecticut. Archived from the original on Feb 18, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Eleanor Tufts; National Museum of Women in the Arts; International Exhibitions Foundation (1987). American women artists, 1830–1930. International Exhibitions Foundation for the National Museum of Women in the Arts. p. 83. ISBN978-0-940979-01-7. Archived from the original on Feb 14, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d east f g "Rotating O'Keeffe exhibit". Fort Worth, Texas: National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame. 2010. Archived from the original on October xiv, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Summertime Days". Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Summertime Days". Whitney Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Saville, Jennifer (1990), Georgia O'Keeffe: Paintings of Hawai'i, Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, p. 13

- ^ Jennings, Patricia & Maria Ausherman, Georgia O'Keeffe'due south Hawai'i, Koa Books, Kihei, Hawaii, 2011, p. three

- ^ Papanikolas, Theresa, Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams, The Hawai'I Pictures, Honolulu Museum of Art, 2013

- ^ Severson, Don R. (2002), Finding Paradise: Island Art in Individual Collections, University of Hawaii Press, p. 119

- ^ a b Tony Perrottet (November 30, 2012), O'Keeffe's Hawaii Archived December ii, 2012, at the Wayback Machine New York Times.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe Paints Hawaii". National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved Apr ix, 2020.

- ^ Severson, Don R. (2002), Finding Paradise: Island Art in Private Collections, University of Hawaii Printing, p. 128

- ^ a b Porter'southward photograph, Eroded Clay and Rock Flakes, Black Identify, New Mexico, July 20, 1953, on cartermuseum.org, in the Amon Carter Museum Eliot Porter Collection Archived Baronial 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved June 16, 2010

- ^ "The White Place in Sun, 1943". Fine art Plant of Chicago. Archived from the original on February i, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Nancy Hopkins Reily (2009). Georgia O'Keeffe, a Individual Friendship: Walking the Abiquiu and Ghost Ranch land. Sunstone Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN978-0-86534-452-five. Archived from the original on February xiv, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Nancy Hopkins Reily (2009). Georgia O'Keeffe, a Private Friendship: Walking the Abiquiu and Ghost Ranch state. Sunstone Press. p. 325. ISBN978-0-86534-452-5. Archived from the original on Feb fourteen, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Biography". Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Archived from the original on November fifteen, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ Jack Salzman (1990). American Studies: An Annotated Bibliography 1984–1988. Cambridge University Printing. p. 112. ISBN978-0-521-36559-eight. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Georgia O'Keeffe Identify Setting, Brooklyn Museum, archived from the original on June 20, 2015, retrieved June 5, 2015 .

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved Jan 18, 2017.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe at Tate Mod Review". Pattern Curial. Oct x, 2016. Archived from the original on February two, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe". Instruction, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved January twenty, 2017.

- ^ "The Flowers and Bones of Georgia O'Keeffe: A Research-Based Dissertation Culminating in a Total-Length Play: Days with Juan - ProQuest". www.proquest.com . Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Marilyn Hall (1978). "Sexist Fine art Criticism: Georgia O'Keeffe: A Instance Written report". Signs. 3 (3): 681–687. ISSN 0097-9740.

- ^ "Sexual activity, Stieglitz and Georgia O'Keeffe | art | Agenda | Phaidon". world wide web.phaidon.com . Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe: Inevitable Icon - ProQuest". www.proquest.com . Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Special Collections Research Centre Knowledgebase".

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Affiliate O" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on June xiii, 2011. Retrieved April fourteen, 2011.

- ^ The National Showtime Ladies Library (2010). Heroes of the Presidential Medal of Freedom (PDF). Canton Ohio. p. three. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved February eleven, 2011.

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887–1986)...Presidential Medal of Freedom received Jan 10, 1977

- ^ John F. Matthews (June 15, 2010). "O'Keeffe, Georgia Otto". Handbook of Texas Online. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Brennan, Marcia (2002). Painting Gender, Constructing Theory: The Alfred Stieglitz Circle and American Formalist Aesthetics . MIT Press. ISBN0-262-52336-1.

- ^ Lynes, Barbara (1989). O'Keeffe, Stieglitz and the Critics, 1916–1929. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN0-8357-1930-8.

- ^ McKenna, Kristine (June 2, 1991). "The Immature and the Restless : O'Keefe & Stieglitz: An American Romance, Past Benita Eisler (Doubleday: 560 pp.)". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Hunter Drohojowska-Philp (2005). Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe. W. West. Norton. pp. 5–6. ISBN978-0-393-32741-0. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved Jan 20, 2017.

- ^ Jonathan Stewart (2014). Walking Away From The Land: Modify At The Crest Of A Continent. Xlibris Corporation. p. 319. ISBN978-i-4931-8090-5. Archived from the original on February xiv, 2017. Retrieved Jan xx, 2017. [ self-published source ]

- ^ Abrams, Dennis. O'Keeffe, Georgia. 2009. Georgia O'Keeffe. Infobase Publishing, p. 97

- ^ A like remark is registered in "Her Story and Her Work" Archived October 29, 2011, at the Wayback Car by Bill Long, vi/29/07.: "I painted it frequently enough thinking that, if I did and then, God would give it to me."

- ^ a b Victor J. Danilov (2013). Famous Americans: A Directory of Museums, Historic Sites, and Memorials. Scarecrow Printing. p. 17. ISBN978-0-8108-9186-9. Archived from the original on February fourteen, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Dennis Abrams; Georgia O'Keeffe (2009). Georgia O'Keeffe. Infobase Publishing. p. 100. ISBN978-1-4381-2827-6. Archived from the original on Feb xiv, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Kilian, Michael (August one, 2002). "Santa Fe exhibit paints a dissimilar picture of O'Keeffe". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

... her place, through the eyes and lens of her close and longtime friend, lensman Todd Webb (1905–2000), who produced a glorious collection of photos of her and her surroundings at her Ghost Ranch and Abiquiú houses between 1955 and 1981.

- ^ Zimmer, William (Dec 31, 2000). "Art; Exploring the Affinities Amid Painting, Music and Dance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved Oct 10, 2010.

O'Keeffe'southward prickly personality is legendary, but with Webb she displays the kind of quietness and at-home she wanted to embody.

- ^ "Who Was Georgia O'Keeffe's Younger Human, Juan Hamilton?". Artdex. Jan 26, 2021. Retrieved September xvi, 2021.

- ^ Asbury, Edith Evans (March 7, 1986). "Obituary: Georgia O' Keeffe Expressionless at 98; Shaper of Modern Art in U.Southward." The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d eastward Carol Kort; Liz Sonneborn (2002). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. New York: Facts on File. p. 171. ISBN0-8160-4397-iii.

- ^ "Settlement Is Granted Over O'Keeffe Manor". The New York Times. Associated Press. July 26, 1987. Archived from the original on February xv, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Anne Dingus. "Georgia O'Keeffe". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on September 6, 2007. Retrieved January 3, 2007.

- ^ Vaughn W. Henry (May ten, 2004). "Establishing a Value is Important!". Planned Giving Design Centre, LLC. Archived from the original on Feb 13, 2007. Retrieved January iii, 2007.

- ^ Jules Heller; Nancy Heller (1995). Northward American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Lexicon . Garland. p. 416. ISBN978-0-8240-6049-7. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved March six, 2020.

- ^ Hunter Drohojowska-Philp (2005). Full Blossom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe. W.W. Norton. pp. four–v. ISBN978-0-393-32741-0. Archived from the original on February xiv, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Alexandra Lange (June 23, 2017). "Jane Jacobs, Georgia O'Keeffe, and the Ability of the Marimekko Dress". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ "Mary Beth Edelson". The Frost Art Museum Cartoon Project. Archived from the original on January eleven, 2014. Retrieved Jan xi, 2014.

- ^ "Mary Beth Adelson". Clara – Database of Women Artists. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Women in the Arts. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Postage Series". Us Mail service. Archived from the original on August ten, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Mod Art in America 1913–1931, Forever". USPS. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Sterling J Nesbitt1, and Mark A Norell (May 7, 2006). "Extreme convergence in the body plans of an early suchian (Archosauria) and ornithomimid dinosaurs (Theropoda)". Proc Biol Sci. The Royal Club. 273 (1590): 1045–1048. doi:ten.1098/rspb.2005.3426. PMC1560254. PMID 16600879.

- ^ "The Most Expensive Female Artists 2016 – artnet News". artnet News. May 24, 2016. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ Susan Rex (July fourteen, 1991). "Focus : Georgia on Her Mind : Jane Alexander'southward Fascination With Creative person O'Keeffe Leads to PBS' 'Playhouse'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Georgia O'Keeffe". Lifetime Television set's. Archived from the original on August xxx, 2009.

- ^ Vincent Terrace (2010). The Yr in Television, 2009: A Catalog of New and Standing Series, Miniseries, Specials and Goggle box Movies. McFarland. p. 59. ISBN978-0-7864-5644-4. Archived from the original on Feb fourteen, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

Farther reading [edit]

- Eldredge, Charles C. (1991). Georgia O'Keeffe . New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN978-0-8109-3657-7.

- Haskell, Barbara, ed. (2009). Georgia O'Keeffe: Brainchild. Whitney Museum of American Art. New Oasis, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-14817-vi.

- Hogrefe, Jeffrey (1994). O'Keeffe, The Life of an American Fable. New York: Runted. ISBN978-0-553-56545-4.

- Lisle, Laurie (1986). Portrait of an Artist. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN978-0-671-60040-2.

- Lynes, Barbara Buhler (1999). Georgia O'Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Fine art. ISBN978-0-300-08176-iii.

- Lynes, Barbara Buhler; Poling-Kempes, Lesley; Turner, Frederick Westward. (2004). Georgia O'Keeffe and New Mexico: A Sense of Place (tertiary ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press. ISBN978-0-691-11659-4.

- Lynes, Barbara Buhler (2007). Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections. Harry Northward. Abrams. ISBN978-0-8109-0957-1.

- Lynes, Barbara Buhler; Phillips, Sandra S. (2008). Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Natural Affinities. Fiddling, Brown and Visitor. ISBN978-0-316-11832-iii.

- Lynes, Barbara Buhler; Weinberg, Jonathan, eds. (2011). Shared Intelligence: American Painting and The Photo. University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-26906-four.

- Lynes, Barbara Buhler (2012). Georgia O'Keeffe: Life & Work. Skira. ISBN978-88-572-1232-6.

- Merrill, C. South. (2010). Weekends with O'Keeffe. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN978-0-8263-4928-6.

- Messinger, Lisa Mintz (2001). Georgia O'Keeffe. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN0-500-20340-seven.

- Montgomery, Elizabeth (1993). Georgia O'Keeffe. New York: Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-0-88029-951-0.

- Orford, Emily-Jane Hills (2008). The Creative Spirit: Stories of 20th Century Artists. Ottawa: Baico Publishing. ISBN978-1-897449-eighteen-9.

- Patten, Christine Taylor; Cardona-Hine, Alvaro (1992). Miss O'Keeffe. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN978-0-8263-1322-5.

- Peters, Sarah West. (1991). Becoming O'Keeffe. New York: Abbeville Printing. ISBN978-1-55859-362-six.

External links [edit]

- Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Collections Online

- Georgia O'Keeffe at the Museum of Modernistic Art

- Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O'Keeffe Archive at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- "O'Keeffe!", a solo role player play by Lucinda McDermott, Playscripts, Inc.

- Works past or near Georgia O'Keeffe in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Works by Georgia O'Keeffe at Open Library

- Georgia O'Keeffe, Archives of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgia_O%27Keeffe

0 Response to "Visual Art in Outdoor Setting Nov 2019 Sc or Ga"

Post a Comment