what, according to burke, did the french do when they overthrew their monarchy?

This slice is a part of our ongoing series, entitled "Rethinking the Revolutionary Canon."

Past Salih Emre Gercek

Republic's fiercest opponents are responsible for its revival as a mod thought. In his Reflections on the Revolution in French republic,[1] in the autumn of 1790, Edmund Burke declared that the French Revolution was bringing commonwealth dorsum for mod times. For Shush, this was an alarming development. He called this "new commonwealth"(71) a "monstrous tragicomic scene"(9) – monstrous considering it was deforming the trunk politic, tragicomic because in its attempts to establish republic it was undermining democracy's ain principles.[2]

Historians of the French Revolution and commonwealth might object to Burke's portrayal of the Revolution as a democratic revolution. By the time the Reflections was published, Revolutionaries had abolished aristocratic privileges, only constitutional monarchy was still a likely pick. They did non call themselves "democrats," using instead other terms such as "patriots," "nationals," and "republicans."[3] Information technology was not until Robespierre's oral communication in 1794 that the Revolutionary government alleged itself to be a "republican or democratic government" in some official form, but even in this case Robespierre used republic not to refer to people's directly involvement in self-regime but to the election of representatives.[4]

Why, then, did Burke identify the French Revolution as a democratic revolution? At showtime, Burke seems to claim that the revolutionary regime is democratic only in facade. "I do non know under what description to class the present ruling authority in France… Information technology affects to be a pure democracy, though I think it is in a direct train of becoming shortly a mischievous and ignoble oligarchy."(109) Burke here seems to suggest that democracy is a cover for an oligarchic class rule in France. Yet, he immediately goes on to say that democracy is emerging in France, and it is speedily on its style to degenerating into a tyrannical government of the masses. "If I retrieve rightly, Aristotle observes that a democracy has many hitting points of resemblance with a tyranny. Of this I am certain, that in a democracy the majority of citizens is capable of exercising the most cruel oppressions upon the minority whenever stiff divisions prevail in that kind of polity."(109-ten) Thus, Burke presents the revolutionary authorities as, on the one paw, an oligarchy pretending to be a democracy, and, on the other hand, a true democracy, in which the masses do tyranny through "popular persecution."(110)

How to reconcile these two claims? How does the rule of the masses turn into the rule of the wealthy? This perplexing picture is precisely what Burke aims to present. With his association of republic with an inherent tendency toward "oligarchy," Shush advances a particular criticism: that democracies in modern times would, ultimately, surrender political power to "new monied interest."(96)

Shush'southward get-go targets are the masses and the "political men of the letters."(97) He starts with reiterating one of the oldest criticisms confronting democracies – that democracy is the rule of the "swinish multitude."(69) By disseminating political power to everyone, democracy diminishes the force of feelings and mores that serve as checks on the abuse of political power. Shush writes: "The share of infamy that is likely to fall to the lot of each private in public acts" is inversely related to number of people who exercise ability.(82) Nevertheless, the problem is non only ane of numbers. It is also a matter of which social class gets a share in political power. To the Chancellor of France's proclamation that "all occupations are honorable," Burke notoriously responds that "the occupation of a pilus-dresser, or of a working tallow-chandler cannot be a matter of award to any person."(43) These classes, "wholly unacquainted with the [political] globe," accept "nothing of politics just the passions they excite" – passions that are destructive, contemptuous, and misguided.(11) With this stance, Burke goes and then far as to say that the power of the masses renders democracy "the nearly shameless matter in the earth."(82)

The power of the masses means the power of the public opinion, and the power of the individuals or parties who can muster and direct public stance. This takes Shush to his next target – the "political men of letters." In France, these "men of messages" "became a sort of demagogues," leading the popular insurgency with their propagation of principles such as natural rights, equality, and pop sovereignty.(98) Many times, Burke attempts to discredit these principles as abstract, devoid of practical wisdom, excessive, and uncompromising. For instance, against the abstract principle of the "rights of men," he poses the "real rights of men" which spring from conventions, manners, and historically accumulated wisdom.(51-three, original emphasis)

The danger with the "abstruse" principles of the Revolution is that they tin can easily exist misdirected in the hands of leading classes. For Burke, this is precisely where the political ascent of the "new monied involvement" lies: "By the vast debt of France, a great monied interest had insensibly grown upwards, and with it a great power."(95) Burke here locates an emerging source of socio-economic power that is in direct disharmonize with landed property: credit. Burke laments: "Everything human and divine was sacrificed to the idol of public credit."(34) Since the nobility and its exclusive "power of perpetuating" the landed property represented the orderly permanence of the ancien régime(45), the creditors could ally themselves with the revolutionaries. The alliance of the dissident "men of messages" and creditors non only brought together "obnoxious wealth" and "desperate and restless poverty"(98) but likewise directed the popular "envy against wealth and power" against the landed nobility and ecclesiastical corporations.(99)

This ironical combination demonstrates how modern democracies are vulnerable, if not accommodating, to the preponderant influence of capital letter. For this reason, Burke was ready to declare as early equally 1790 that the democratic revolution in French republic would lead to its own demise towards a corrupt oligarchy. After the abolitionism of feudal rights in August 1789, he saw no collective social power such every bit the church building or nobility to obstruct and remainder the power of, first, the masses, and later, the monied form. Tragicomically, democracies cease up undermining their ain egalitarian imperatives.

In a further historical irony, many of things that Burke criticized about democracy afterward became means of enervating or defending it. Against Burke's criticism that democracy breeds popular contempt towards upper classes, Mary Wollstonecraft defended such contempt against those who owe their position to capricious social hierarchies.[5] In the hands of démocrates such every bit Jean-François Varlet and Gracchus Babeuf, Burke's denunciation of the new monied interest and their political power turned into a demand for, respectively, direct democracy and "de facto equality."[6] Conversely, in the early nineteenth-century, when this short-lived democratic radicalism was suppressed and democracy came to exist associated with representative government, Benjamin Constant went completely against Shush by celebrating credit as the all-time restraint confronting the power of governments.[7] These examples illustrate one indicate: While Burke's Reflections aimed to thwart preemptively any possible enthusiasm for the idea of democracy, it became one of the virtually perceptive works on the subject area. This is 1 of the most peculiar aspects of the history of democracy: its revival every bit a modern idea was pioneered by its fiercest opponents as much as its supporters.

Salih Emre Gercek is a doctoral candidate in political theory at Northwestern University. His dissertation considers how the idea of democracy emerged and evolved against the groundwork of the "social question" in nineteenth century political thought.

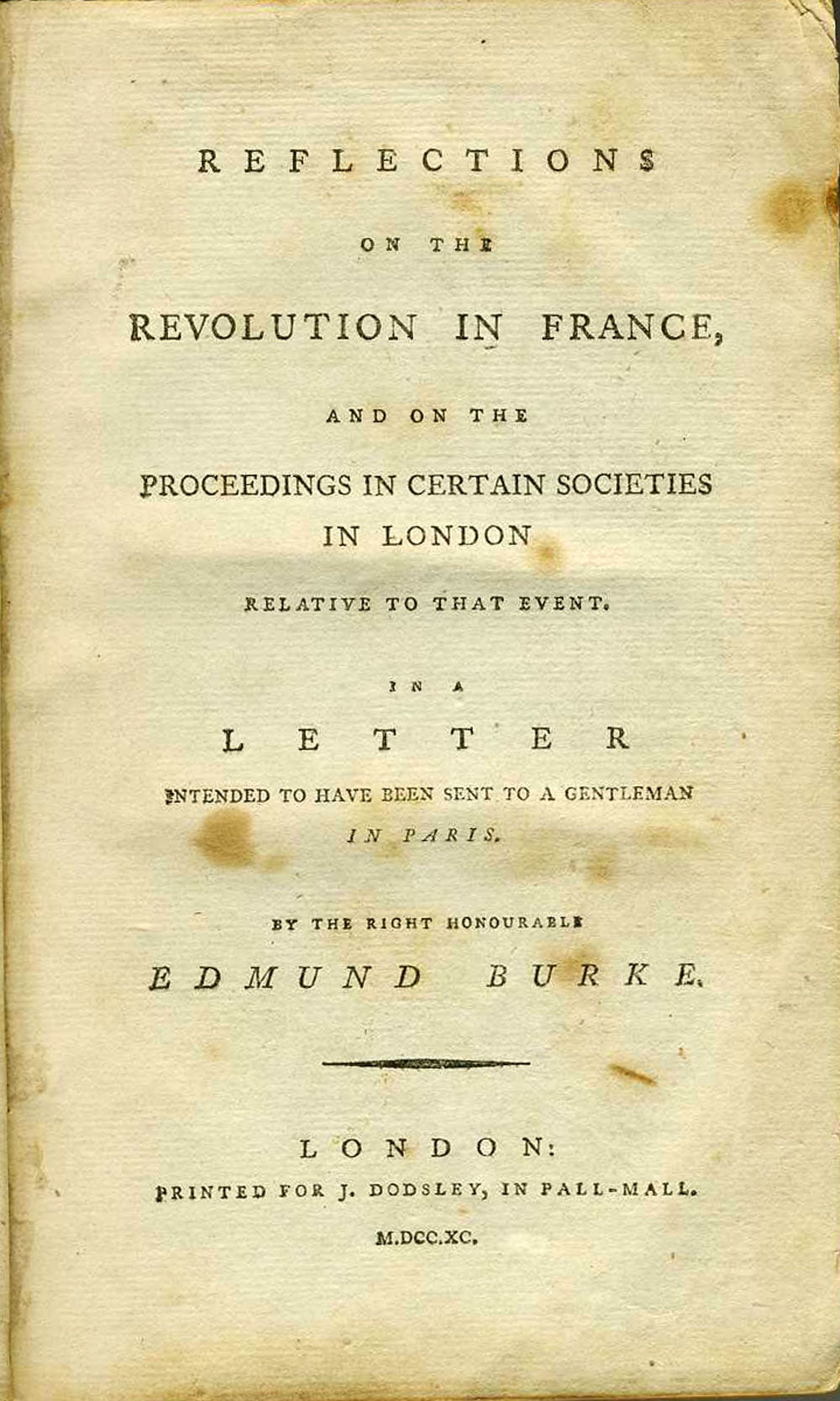

Title image: Frontispiece to Reflections on the French revolution. France, 1790. London: Pubd. past Willm. Holland No. 50 Oxford St., in whose rooms may exist seen the largest collection in Europe of caricatures, acknowledge 1 sh., November. the 2. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/detail/2004669854/.

Further Readings:

Bourke, Richard. "Enlightenment, Revolution and Democracy," Constellations fifteen.1 (2008): 10–32

Dunn, John. Republic: A History (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2005).

Hampsher-Monk, Iain. "Rhetoric and Opinion in the Politics of Edmund Shush," History of Political Idea 9.3 (1988): 455-484.

Innes, Joanna and Philp, Marking (eds).Re-imagining Democracy in the Age of Revolutions: America, France, Britain, and Ireland, 1750-1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Menke, Christoph. Reflections of Equality, trans. H. Rouse and A. Denejkine (Stanford: Stanford Academy Press, 2006), Chapter 5.

Palmer, R.R. The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Printing, 2014).

Pocock, J.G.A. "The Political Economy of Burke's Analysis of the French Revolution," The Historical Periodical, 25.2 (1982): 331-349

Endnotes:

[one] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, ed. J. G. A. Pocock (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co, 1987). In text references indicate the page numbers.

[2] On the polemical nature of the give-and-take republic in America, run into Matthew Rainbow Hale'due south post on this blog: https://ageofrevolutions.com/2018/07/16/defining-democracy-challenging-democrats/

[three] R. R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014); Pierre Rosanvallon, "The History of the Word 'Commonwealth' in France," Periodical of Democracy, vi.4 (1995): 140-54.

[4] Maximilien Robespierre, Sur le principe de morale politique qui doivent guider la convention nationale dans fifty'assistants intérieure de la république, Textes Choisis, Tome Troisième, ed. Jean Poperen (Paris: Editions Sociales, 1974). On Robespierre's redefinition of democracy as a representative authorities, run into Kathlyn Marie Carter's mail on this blog: https://ageofrevolutions.com/2018/07/23/the-invention-of-representative-democracy/

[5] Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and A Vindication of the Rights of Man, ed. Janet Todd (Oxford: Oxford Academy Printing, 2009).

[half-dozen] Jean-François Varlet, Du Plessis. Le Malheur, Quelle École ! Ce Que j'écris La Nuit, à La Lueur Obscure d'une Lampe de Prison En Est Peut-Être Une Preuve. Tyrans Ou Ambitieux, Lisez… (Paris, 1794); Philippe Buanorroti, Histoire de La Conspiration Pour fifty'égalité Dite de Babeuf, Suive Du Procès Auquel Elle Donna Lieu (Paris: Chez G. Chavaray Jeune, 1850).

[7] Benjamin Abiding, "The Freedom of the Ancients compared with that of the Moderns," Political Writings ed. Biancamaria Fontana (Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press, 1988), 309-28.

Source: https://ageofrevolutions.com/2019/06/03/why-did-edmund-burke-call-the-french-revolution-a-democratic-revolution/

0 Response to "what, according to burke, did the french do when they overthrew their monarchy?"

Post a Comment